An interview with Christian Humborg, one of two Executive Directors of Wikimedia Deutschland, about the new association Wikimedia Europe incorporating 22 European member organizations.

Why is it important for the Wikimedia movement to get involved at the European level as well?

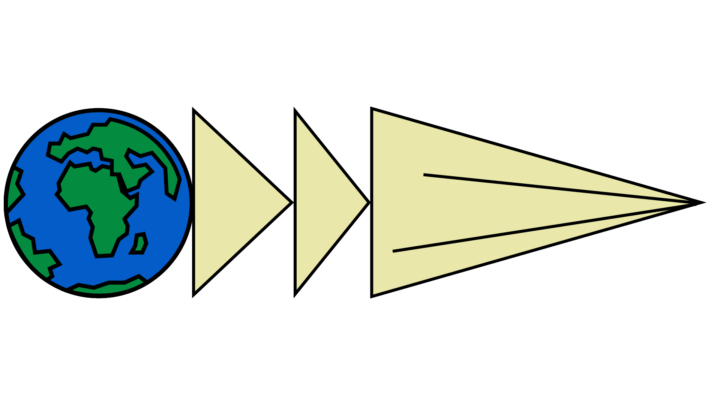

Christian Humborg: First of all, we are a global movement, so it is part of our DNA to think internationally. The boundaries we deal with in our contexts are usually not geographical, but linguistic. After all, Wikipedias are organized by language, not by country. In my view, anybody confronted with the decision: Europe or Germany? nowadays would have to give very good reasons not to choose Europe. Europe is the political future. And if we want to create Free Knowledge in a free world, Europe is exactly the right place.

Until now, the advocacy group in Brussels was the Free Knowledge Advocacy Group Europe (FKAGEU). How was it positioned?

For many years, FKAGEU has been very successful in representing the interests of the members of our movement with two staff members in Brussels and has covered a wide range of topics, including the dispute about net neutrality, the question of platform regulation, but also more specific topics such as freedom of panorama. We have to acknowledge that on issues important to us, more decisions are now made at the European rather than the national level. If we want to influence political decisions in our subject areas, we have to position ourselves there as well. When European laws are transposed into national law, it is sometimes too late to make a difference.

What provided the impetus for founding Wikimedia Europe?

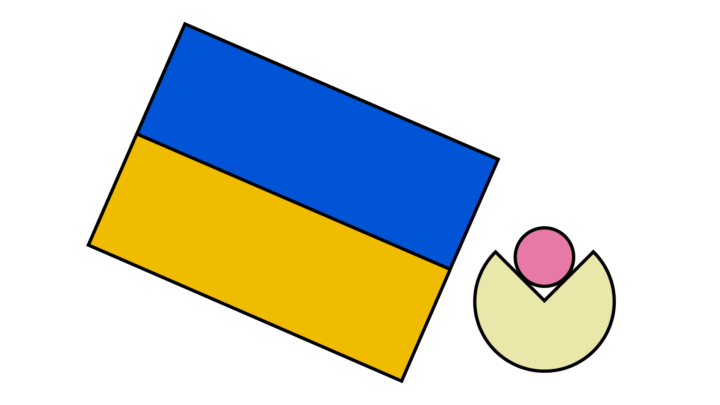

First of all, it is clearer for local policymakers to be addressed by Wikimedia than by an organization with the acronym FKAGEU. However, the underlying idea is the real determining factor: On the one hand, Wikimedia Europe became a body in its own right, registered as an advocacy group in Brussels and thus also entitled to acquire European funding, which had not been possible before. And secondly, there is now a formal governance structure on the ground that defines how decisions are made and who is a member of Wikimedia Europe. We have thus achieved a level of professionalism that allows us to have a stronger presence and act accordingly.

How did the founding process go?

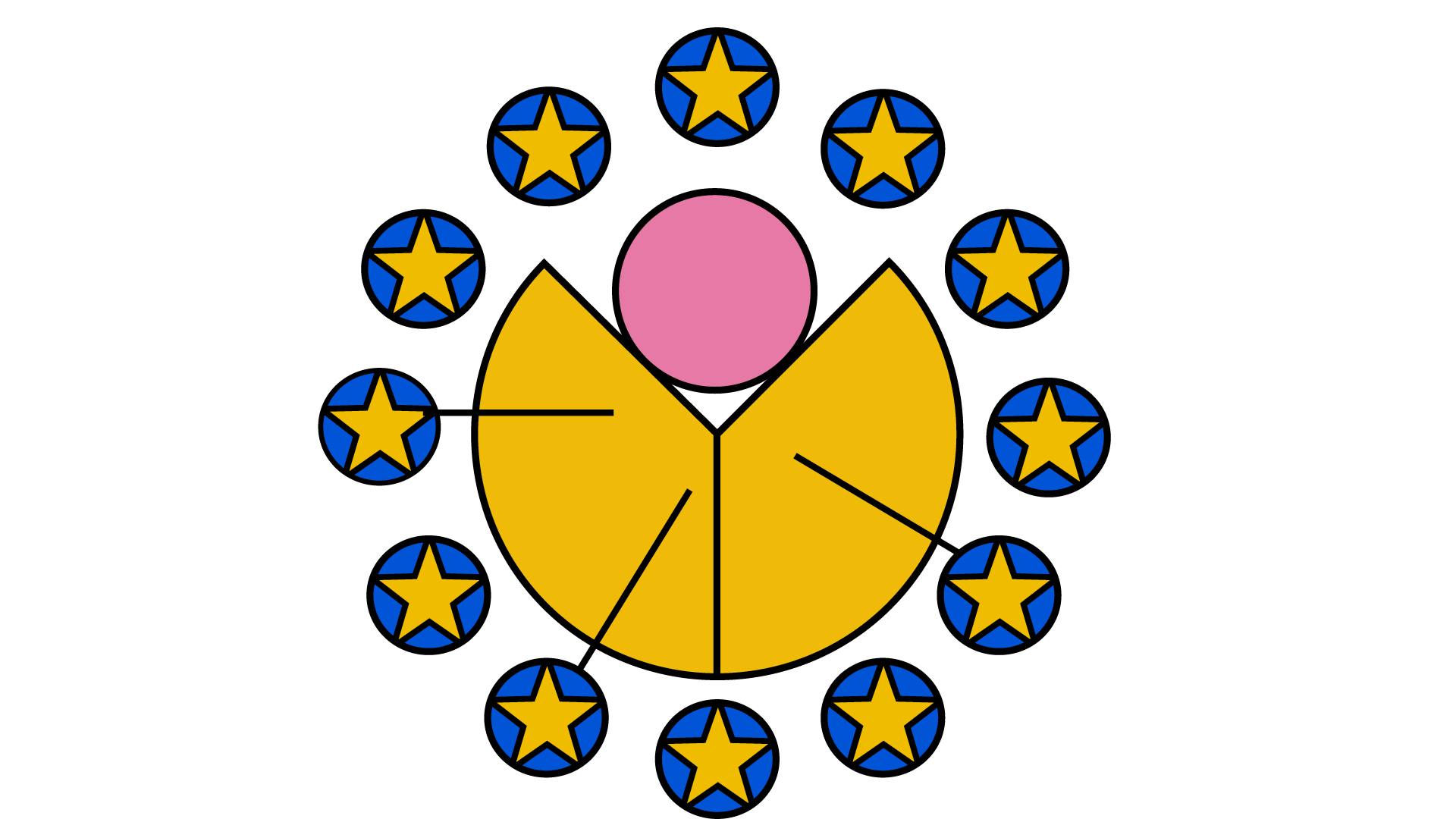

Talks about bringing Wikimedia Europe into being have been going on for years. In 2021, we finally reached a breakthrough when a group of member organizations decided to move forward with the project in a concrete way. Wikimedia Deutschland was among them, but also Wikimedia Switzerland, Austria, the Netherlands, France and others. One of the decisions was to found Wikimedia Europa if at least six affiliates join. Six – that was also the founding number of the European Economic Community at the end of the 1950s. In the end, 22 organizations participated, exceeding the original expectations by far.

What were the next steps?

In a series of video conferences, we then clarified what our statutes should look like and where the organization’s headquarters should be located, who could be a member, and which topics we wanted to work on together. We then reached the point of being able to apply to the authorities of Belgium’s King for approval. The formal seat of our organization is in Brussels, the annual general assemblies are held in Prague. Eastern European affiliates in particular have rightly pointed out that Brussels is not in the heart of Europe, which is why we have found a good and practical compromise.

What gives Wikimedia Europe its power?

We have to acknowledge that in today’s world, it is initially the name that has a powerful impact. A presence as Wikimedia Europe is a strong political signal – because it covers the region in the world that particularly stands for the pursuit of freedom and democracy, as does the European Union.

What are the political priorities in Brussels?

Important issues will always remain net neutrality, copyright and freedom of expression and information, also platform regulation – always looking to make sure Wikipedia is not forgotten. European policymakers usually have Facebook, TikTok or Instagram in mind when it comes to platforms – and often forget that adopted regulations must also be met by Wikipedia volunteers. We also need to look at the digital commons, i.e. the question of how we can preserve and expand the public space in the digital sphere, of which Wikipedia is a part. Unlike in the analogue sphere, in the digital world we move almost exclusively in commercial fields. It’s about developing a vision for what a better digital world can look like.

What is Wikimedia Europe’s perspective?

I would like Wikimedia Europe to become an important player in sociopolitical debates about digital matters at a European level. In the same way, I would like to see more opportunities for many organizations and volunteers to get financial support. It goes without saying that we support theatres and museums in the analogue space. If we don’t just want commercialization in the digital realm, we have to fund an adequate public infrastructure for this purpose. Wikimedia Europe can play an important role in this context.